Author

Yoan Kolev

The Bulgarian lev: A farewell to a national currency

Money in the Bulgarian lands from the 16th to the 21st century

Thursday 1 January 2026 07:40

Thursday, 1 January 2026, 07:40

PHOTO BGNES

Font size

One hundred and forty-five years after being introduced, the lev is being phased out and replaced by the euro as Bulgaria's official currency.

The lev officially entered circulation on 4 June 1881. On the same date in 2025, the European Commission and the European Central Bank, in their extraordinary convergence reports, announced that Bulgaria is ready to join the euro area as of 1 January 2026.

What is the history of the Bulgarian lev?

One of the first things the young Bulgarian state gained after its liberation from the Ottoman Empire in 1878 — and a key step in asserting its sovereignty — was the right to have its own currency.

In 1880, the National Assembly passed the Law on the Right to Mint Coins in the Principality, establishing the Bulgarian national monetary unit: the lev. From 1885, the Bulgarian National Bank (BNB) was granted the right to issue banknotes backed by gold, and from 1891, by silver too.

Bulgaria’s national currency was printed in renowned printing houses in Great Britain, Russia, Germany and France.

PHOTO bnb.bg

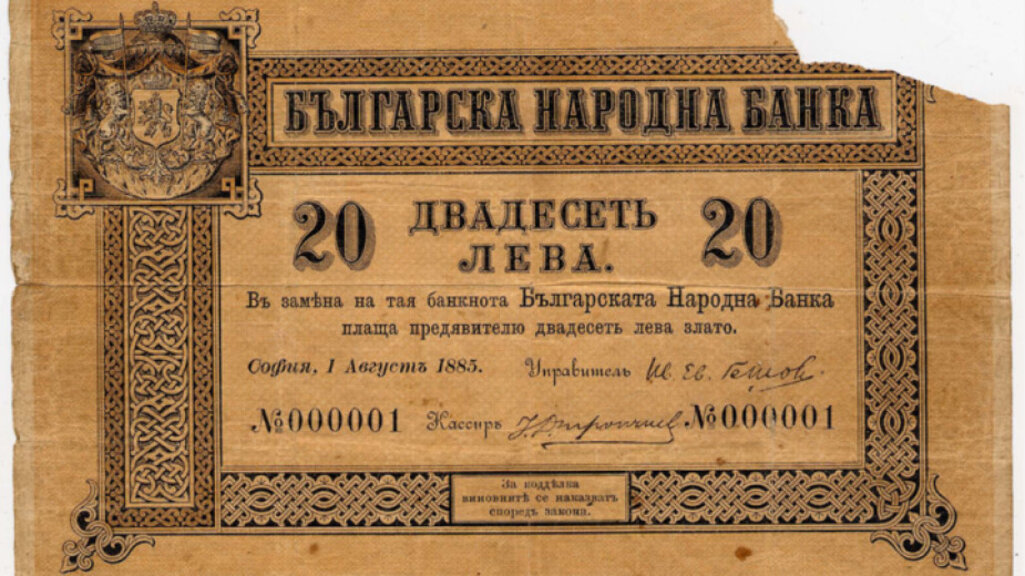

The first banknote, bearing the serial number 000001, was printed on 1 August 1885 in Saint Petersburg, Russia. Its denomination was 20 leva, and its dimensions were 150 by 97 millimetres. The left corner of the note featured a watermark of the Bulgarian National Bank. The original first Bulgarian banknote is preserved in the Historical Museum of Gabrovo.

The first Bulgarian banknote.

PHOTO Regional Historical Museum in Gabrovo

Historians suggest that the Dutch leeuwendaalders (lion thalers), which appeared in the Bulgarian lands in the 17th century, may have served as a prototype for the Bulgarian lev.

'The leeuwendaalder was certainly known to the Ottomans and was used within the Ottoman Empire during the 16th and 17th centuries, says Hristiyan Atanasov, a lecturer in the Department of Political Economy at the University of National and World Economy. - The Ottomans were part of the so-called 'silver world', which also included India and China, where silver coinage predominated.'

Hristiyan Atanasov

PHOTO Facebook/ Hristiyan Atanasov

During the 16th and 17th centuries, the Ottomans mainly used the akçe as a coin, but it quickly depreciated and came to be used primarily as an accounting unit.' Gradually, Dutch, German and Czech thalers entered the market in large numbers and became very popular with the local population in the Balkans. Most likely because they were large coins featuring a lion’s head, these thalers can be considered a prototype of the Bulgarian lev. They continued to circulate in Ottoman markets — and particularly in Bulgarian territories — up until the Liberation.'

Alongside its own Ottoman currency, the kurush, the empire saw the use of a vast number of coins from different states.

PHOTO wikipedia.org

“It was silver and relatively large, subdivided into grosz, para, and akçe. In 1844, a gold–silver standard was adopted, and they began minting gold lira, which were strictly pegged to the silver grosz. This standard remained in place until the end of the Ottoman empire after the First World War. During and after various wars — the Crimean War, the Russo-Turkish War and the First World War — they also issued paper money called kaime to cover budget deficits.

In other words, by the time the Bulgarian lev was introduced, experience had already been gained with both the gold–silver standard and paper money. This experience carried over after the Liberation, when the 1880 Law on Minting the Bulgarian Lev was adopted, linking it to the French franc. Paper money also began to be issued, but, based on historical experience, it was received with great distrust by the population, who remembered what had happened with Ottoman kaime and its rapid depreciation,” Mr Atanasov says.

The first Bulgarian gold leva appeared in 1894. It remained in circulation for only a short time, until the First World War.

PHOTO reddit.com

'At the time, the Ministry of Finance preferred to mint silver leva because the state could generate additional revenue through seigniorage—the profit made from the difference between the cost of producing money and its face value. Consequently, Bulgaria did not adopt a long-term gold standard.'

From the Liberation in 1878 until 1952, all Bulgarian coins were minted abroad. However, our interlocutor does not consider the establishment of the Mint, and Bulgaria’s subsequent right to mint its own currency, to be a particular symbol of independence.

Throughout its history, the Bulgarian lev has always been ‘pegged’ to a foreign currency, he explains. First it was the French franc, then the Russian ruble, the German mark, and since 2002, the euro. The only period when the lev was not tied to a foreign currency was during hyperinflation at the end of the 20th century, which led to the introduction of the Currency Board.

PHOTO BTA

From 1 January 2026, Bulgaria is part of the eurozone. For the first month, both currencies will be used in parallel, after which the lev will remain in history.

'It will certainly have emotional value and become a collector’s item. The lev will continue to be exchangeable at the current fixed rate to the euro (1 EUR = 1.95583 BGN), meaning that even after the period of replacing coins and banknotes with the euro has passed, people will still be able to exchange leva for a long time—whether forgotten or kept for some reason,' explains Hristiyan Atanasov, offering advice to those worried about the current transition from the lev to the euro.

'I know that any change is difficult to accept, but I think people should trust the institutions more, even though I know that is easier said than done. In my view, the process will go smoothly, and I advise people to keep some leva as a memento. At the same time, however, we need to look to the future, and I believe that adopting the euro will lead to a better future for the country,' Hristiyan Atanasov concludes optimistically.

Editor: Elena Karkalanova

Posted in English by E. Radkova

This publication was created by: Elizabeth Radkova